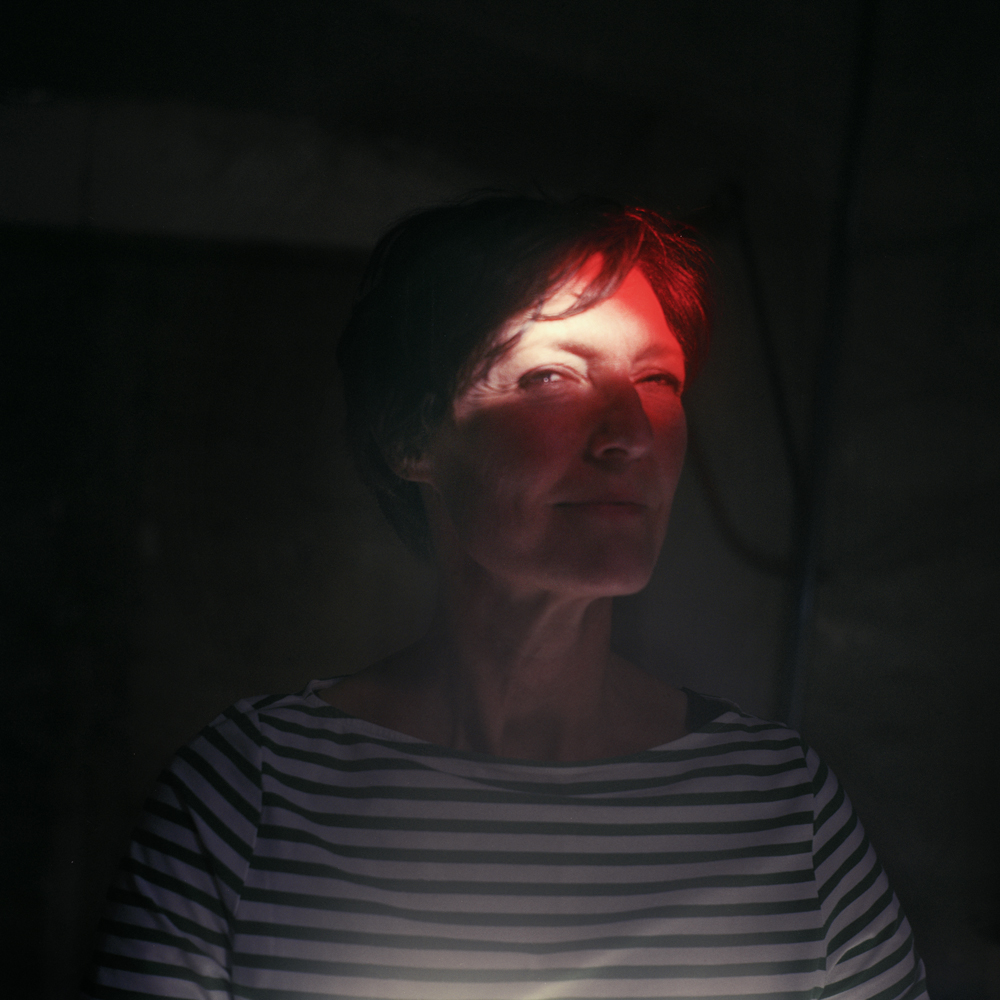

The Taste

of the Wind

2017-2018

Everything is impermanent; change is inevitable. We, as part of a society, should encounter and defy the potential problems that change can result in. Europe is changing. Change should be seen as an opportunity to grow, not only collectively but as an individual. Part of my work as an artist involves denizen stories, objects, artefacts and museum archives that I use as a tool to address changes and, in particular, integration, aiming to make the whole working process of this project a positive experience.

For a period of one year (July 2015 – May 2016), more than one million people applied for asylum in Europe. Sweden is the European country with the highest proportion of asylum seekers per thousand inhabitants, and Landskrona has taken more immigrants and refugees than most cities in the country. However, it is not the first time that Landskrona has sheltered refugees. Landskrona was one of only four towns in Sweden in which Jews, Chileans and people from the Balkans were allowed to reside. Thanks to the support of Landskrona Foto, in May 2017 I arrived in Landskrona to work on this theme. The art residency lasted for six weeks. I spent the first week walking around, collecting documents that could potentially be incorporated in my work and meeting different people based in Landskrona. I wanted to seek different views and gather documents that helped me study and assess the complex society of Landskrona and its political situation.

In the second week, I visited Landskrona Museum’s archive collection. As soon as I walked into the photographic archive room, I was overcome by a sense of being watched by all the photographers who took those pictures. However, most photographs have an unknown author because they were taken by employees of the Landskrona Council. The Council still retains the rights to their work. Browsing through the shelves that contained thousands of photo negatives, I found images of the first refugees in Landskrona. I also found photographs that allowed me to learn about an important historical event for the city: the end of the Swedish shipyard Öresundsvarvet, which happened between 1980 and 1982 and left Landskrona in a financial and social crisis, losing many of its residents.

As soon as I walked into the photographic archive room, I was overcome by a sense of being watched by all the photographers who took those pictures. However, most photographs have an unknown author because they were taken by employees of Landskrona Council. The Council still retains the rights to their work. Browsing through the shelves that contained thousands of photo negatives, I found images of the first refugees in Landskrona. I also found photographs that allowed me to learn about an important historical event for the city: the end of the Swedish shipyard Öresundsvarvet, which happened between 1980 and 1982 and left Landskrona in a financial and social crisis, losing many of its residents.

Foster, H (2004) An Archival Impulse, Massachusetts: MIT Press

Batchen, G. (2004) Forget me not: Photography and remembrance, Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum

From the third week until the end of the art residency, I worked as artist-as-archivist with the idea of ‘not only to represent but to work through, and propose new orders of affective association’ (Foster, 2004). In the context of The Taste Of The Wind, these photographs were linked with a psychological journey between past and present. I took new photographs to complete a Landskrona Family Album with the new family members. A selection from a photographic archive can support our memory, giving us more information about our past and keeping us from forgetting. We usually connect the photographs and the memories as if they were synonymous. Photographs help to replace our memories with images in different ways: informational, coherent and historical (Batchen, 2004). But sometimes we distort the past and create our own stories and images.

Sekula, A (1986) The Body and the Archive in October, vol 39, Massachusetts: MIT Pres

Foad, H (2011) ‘Europe without borders? The effect of the euro on price convergence’, International Regional Science Review, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 86-111.

Younge, G. (2017) ‘End all immigration controls – they’re a

sign we value money more than people’, The Guardian, Available

at: https://www.theguardian.com/ commentisfree/2017/oct/16/end- immigration-controls-money-people- barriers (Accessed: 1 September 2019)

The Taste of The Wind places the emphasis on the politics of the images, on their veracity and on their historical information. As Allan Sekula suggests when writing about the photographic archive, it ‘entails a notion of legal or official truth, as well as a notion of proximity to and verification of an original event’ (Secula,1986). It brings together the acceptance of and participation in of Europe’s changing society. Borders work in a different way in free trade zones like the EU. Every country has a different terminology for border, space and place, as does every European citizen. ‘Differential tax schemes across European countries may matter, as well as language and cultural differences’ (Foad, 2010). A European millennial generation could help to make real the utopian idea of a world without borders. But the newly imposed immigration controls ‘are a sign we value money more than people’ (Younge, 2017). When crossing the Öresund Bridge, the train stops for some time so that the police can check the travellers’ passports. I would like to imagine Europe without border guards, barbed wire, passport controls, walls, fences or barriers. The Europeans would be better people without them.

Selected

exhibitions

The Taste Of The Wind has been exhibited as solo shows in Landskrona Foto Festival 2018 and ArtPhoto BCN 2021

Tyghuset. Landskrona Foto Festival, Sweden. 2018

Carlos Alba

+34 626 159 284 (Spain)

studio@carlosalba.com

This Book Is True

Cristina De Middel & Carlos Alba photo book publishing house

www.thisbookistrue.es

Subscribe!

I won't send you Ads, only good news!